QR Code Scanning & Generation with ZXing and Angular

QR codes provide a very valuable way of sharing information with users, and many applications rely on them for various purposes. Common examples of places where QR codes can be useful include but are not limited to theaters, social gatherings and other booking services. Integrating QR codes can seem intimidating, but thankfully they’re not too difficult to handle with Angular and the help of a couple of robust software libraries such as ZXing.

What is ZXing?

ZXing, also known as “Zebra Crossing” is a software library that allows developers to easily integrate scanning many different types of 1D and 2D barcodes. This library was originally written in Java, however many ports to other languages and platforms exist, including JavaScript.

There are a couple of ways to use ZXing. You could either directly use the JavaScript library, which is framework-agnostic, or you could use a framework-specific library. I’m going to demonstrate how to use ZXing to scan QR codes with the Angular version of the library called ngx-scanner specifically, which has a full-fledged scanner component that makes it somewhat easy to integrate.

Let’s Scan some QR Codes with Angular!

Getting ngx-scanner up and running doesn’t take much setup at all. All you have to do is add an import to ZXingScannerModule inside of the module that you will be scanning QR codes in, and add a component to your template. Below shows a real-world example of how the <zxing-scanner> component would be used.

<zxing-scanner

#scanner

*ngIf="startCamera$ | async"

class="scanner"

[enable]="(enable$ | async) ?? false"

[autostart]="true"

[device]="(selectedDevice$ | async) ?? undefined"

[formats]="allowedFormats"

(camerasFound)="devices$.next($event)"

(scanSuccess)="scanSuccess$.next($event)"

(scanError)="scanError($event)"

></zxing-scanner>

You’ll notice a lot of observables being referenced here. I’ll go over them one by one. Let’s start with the devices subject:

devices$ = new BehaviorSubject<MediaDeviceInfo[]>([]);

This subject has data sent to it whenever cameras have been identified by the scanning component. We want to keep track of these so that we’re able to select a camera to use. In our case we’ll just select the first camera for simplicity's sake, as you can see happens with the selectedDevice$ observable that we have bound to the [device] attribute on the scanner:

selectedDevice$: Observable<MediaDeviceInfo> = this.devices$.pipe(

map((device) => device[0]),

distinctUntilChanged(),

shareReplay(1)

);

We utilize shareReplay here so we don’t need to re-scan the devices whenever additional subscribers check what devices are available.

enable$ is a simple observable that emits true whenever devices have been detected, and startCamera$ is an observable that toggles between true and false whenever data is pushed to the toggleCamera$ subject.

toggleCamera$ = new BehaviorSubject<boolean>(false);

startCamera$ = this.toggleCamera$.pipe(

scan((acc) => !acc, true),

startWith(true)

);

The scan function from RxJs is utilized so we have the previous state and can use that to determine in which direction the stored boolean should toggle to.

Finally we push successfully scanned codes to scanSuccess$ which we can then subscribe to in the template.

All together the final component code should look something like this:

@Component({

selector: 'app-scanner',

templateUrl: './scanner.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./scanner.component.scss'],

})

export class ScannerComponent {

@ViewChild('scanner') scanner!: ZXingScannerComponent;

allowedFormats = [BarcodeFormat.QR_CODE];

devices$ = new BehaviorSubject<MediaDeviceInfo[]>([]);

selectedDevice$: Observable<MediaDeviceInfo> = this.devices$.pipe(

map((device) => device[0]),

distinctUntilChanged(),

shareReplay(1)

);

enable$ = this.devices$.pipe(map(Boolean));

toggleCamera$ = new BehaviorSubject<boolean>(false);

startCamera$ = this.toggleCamera$.pipe(

scan((acc) => !acc, true),

startWith(true)

);

scanSuccess$ = new BehaviorSubject<string>('');

scanError(error: Error) {

console.error(error);

}

}

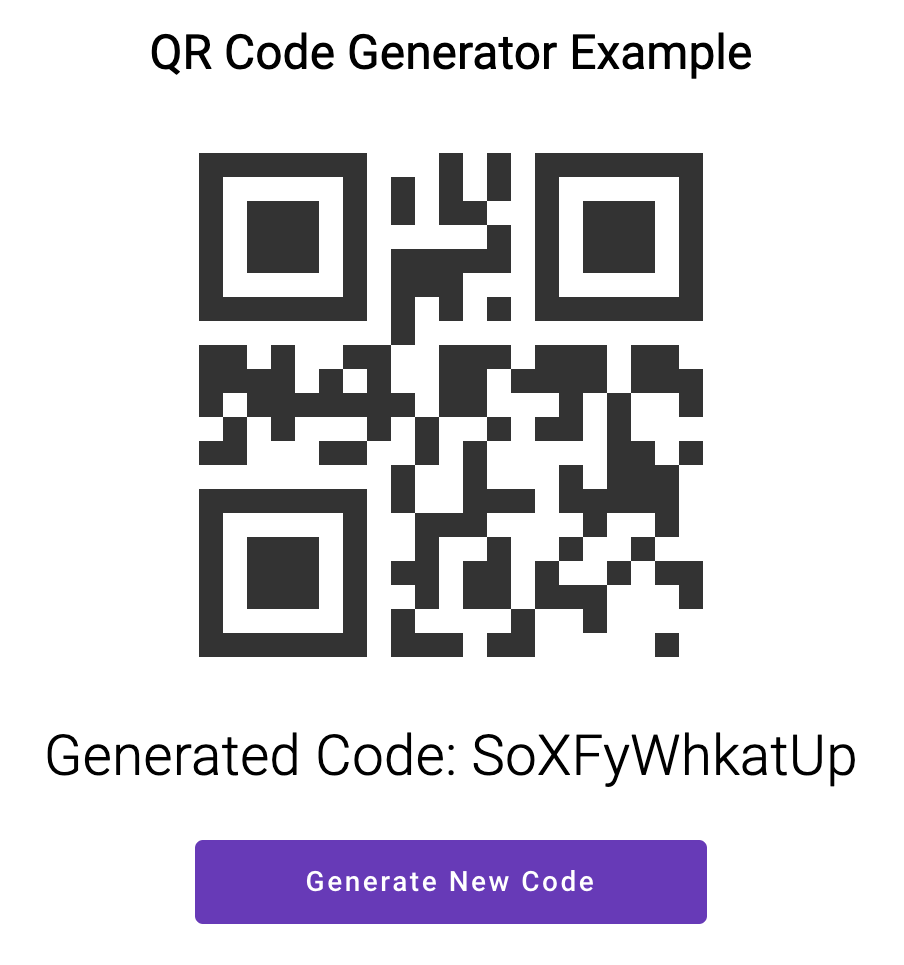

If we use this component then you should get something that looks like this:

Scanning QR codes is awesome, but we can also generate our own QR codes as well!

Generating our own QR Codes

Unfortunately the ZXing scanner component we’re using is limited to just scanning QR codes, however there is another component library called ngx-kjua that can do this. Like ZXing this component is also based off of another pre-existing library that is framework-agnostic, in this case, kjua.

Fortunately kjua is very easy to use. You simply supply it a code and it will render a QR code.

<ngx-kjua

class="code"

*ngIf="code$ | async"

[text]="code$ | async"

[size]="256"

></ngx-kjua>

How the QR code is rendered can change. There is an optional [render] attribute that you can specify that takes a few values. You can input ‘image’, ‘canvas’ or ‘svg’. The default render mode is ‘svg’. It should be noted that ‘svg’ and ‘canvas’ render modes made copying the image more difficult, so use ‘image’ if you want to make that possible.

The component code associated with this template is very small. The component using ngx-kjua has a code observable that is updated with a new random code whenever a “Generate” button is pressed.

import { Component } from '@angular/core';

import { BehaviorSubject } from 'rxjs';

import randomstring from 'randomstring';

@Component({

selector: 'app-generator',

templateUrl: './generator.component.html',

styleUrls: ['./generator.component.scss'],

})

export class GeneratorComponent {

code$ = new BehaviorSubject<string>(this.generateCode());

generateCodeClick(event: MouseEvent) {

this.code$.next(this.generateCode());

}

private generateCode(): string {

return randomstring.generate({ length: 12, charset: 'alphabetic' });

}

}

I’ve opted to go with the randomstring package in this case. This component could be modified to instead allow for custom codes using a textbox if you want to encode URLs or other useful values that typically go inside of QR codes.

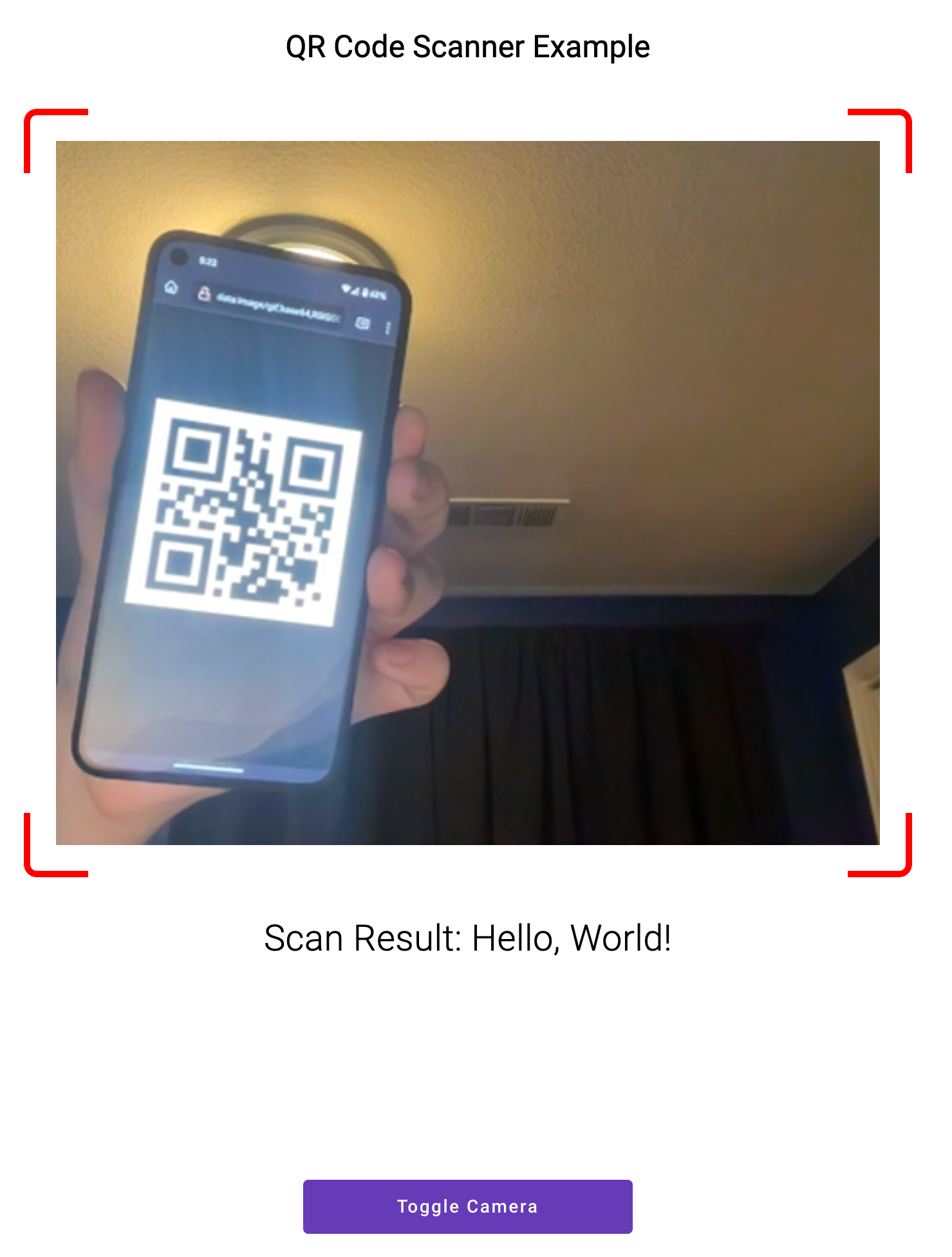

The result looks like this:

Summary

Thanks to projects like ZXing and kjua it is easy to integrate handling of QR codes in Angular applications, be it for scanning them or creating them. I hope this guide has helped you. You can find the full example showcasing generation and scanning of QR codes in our blog-demos repository on GitHub.